International Chairs Course 2025

A six-week online course led by Jnanadhara (International Movement Coordinator)A Life for the Dharma –

Bhante’s 100th

For the last two years Jnanadhara has led these courses as part of his work as International Movement Coordinator; however, this year’s course will have brand new content. As this year is his Centenary we’ll be making the most of the auspicious moment by taking as the theme for our explorations our teacher and founder Urgyen Sangharakshita.

We’ll be delving into different aspects of his life as a Dharmafarer – devotee, mystic, teacher, friend, writer, lover, revolutionary – and see what we can learn from these qualities and activities for our own lives as Dharmafarers working as Chairs. There is rich material to draw on, and there is abundant potential for significant inspirations and insights to pass between us.

Aims for the Course

The aim for these courses is to help us all gain greater clarity, confidence and effectiveness in our work and a deeper understanding of how to approach it so it is a transformative spiritual practice. A wider aim is to bring chairs together across the world in order to build friendships and connections and to know and feel more keenly our unity as an international spiritual community.

The course is not only for new chairs but also for experienced chairs as well – so if you have been a chair for a while please come and share your experience, knowledge and perspective! While it is mainly focussed on running centres the content will be widely applicable, so if you are a director of a charity or team based right livelihood please join us.

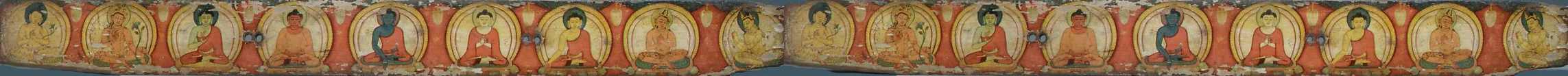

Photo from the Triratna Picture Library

An Overview of the Course

Week 1 – Sangharakshita as Devotee

Resources:

- Bhante’s reflections on the Garava Sutta

- 1981 Q & A with Chairs of centres (the section that I quote from starts on page 4)

- the slides used

The Poem 'Above Me Broods'

Above me broods

A world of mysteries and magnitudes

I see, I hear,

More than what strikes the eye or meets the ear.

Within me sleep

Potencies deep, unfathomably deep,

Which, when awake,

The bonds of life, death, time, and space will break.

Infinity

Above me like the blue sky do I see

Below, in me,

Lies the reflection of infinity.

1947

I had a natural tendency to look up to and to revere what was above me in any way, whether in human life or thought or culture. This is how Bhante, late in life, described his character. We looked at this most basic human quality of reverence and reflected on how it can be an active force in our work.

Week 2 – Sangharakshita as Kalyana Mitra

Resources:

- The full interview with Ratnavandana

- The full interview with Subhuti

- the slides used

Quotations used

from Ariyapariyesanā Sutta

Suppose that, being myself subject to birth, ageing, sickness, death, sorrow, and defilement, having understood the danger in what is subject to birth, ageing, sickness, death, sorrow, and defilement, I seek the unborn, unageing, unailing, deathless, sorrowless, and undefiled supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna.

And while this discourse was being spoken, there arose in the Venerable Kondañña the dust-free, stainless vision of the Dhamma: “Whatever is subject to origination is all subject to cessation.”

from In The Sign of the Golden Wheel – SCWOR Vol 22 page 374

By this time I had developed considerable confidence in the Rimpoche, and I therefore asked him to tell me who my yidam or tutelary deity was. Though unable to accept Dr Mehta’s ‘guidance’ on his (or its) own terms, I had taken very much to heart his insistence that in the spiritual life the best and most reliable guidance was that which came from beyond one’s ego. For me it could not come from God, but perhaps it could come from one or other of those transcendental beings who according to the Buddhism of Tibet (as of that of China and Japan) were the different, infinitely various, aspects of the Buddha’s sambhogakaya or ‘body of glory’ – the supra historical ‘body’ in which he communed with advanced bodhisattvas and they with him. Chattrul Rimpoche showed no surprise at my request. In fact he seemed rather pleased, and after a moment of inner recollection told me that my yidam was Dolma Jungo or Green Tārā, the ‘female’ bodhisattva of fearlessness and spontaneous helpfulness, adding that Tārā had been the tutelary deity of many of the great pandits of India and Tibet. In other words, I had an affinity with Green Tārā, in the sense that she was the transcendental counterpart of my own mundane nature and that I could, therefore, more readily come to a deeper understanding of myself through devotion to her. Having told me my yidam, the Rimpoche proceeded to bestow the appropriate initiation. First he gave me the ten-syllabled mantra, which he pronounced very forcibly in the Tibetan manner, after which he explained the sādhana or spiritual practice that would enable me to visualize Green Tārā and call down her blessings on myself and all sentient beings. The latter he did at some length, so that it was mid-afternoon when I finally bade him a grateful farewell, having spent more than four hours in his company. My mood was one of considerable elation.

from Kalyana Mitra Yoga

“I entreat you, O Buddha Shakyamuni, revealer of the Dharma,

and you, great Gurus of the Past and Present, who are a source of inspiration,

and you, Urgyen Sangharakshita, who have given me the gift of the Dharma,

please witness my Going for Refuge to the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha,

and grant me your blessings.”

from The Ten Pillars

Just as killing represents the absolute negation of another person’s being, ‘love’ as we must perforce call it represents its absolute affirmation. As such it is not erotic love, or parental love, or even friendly love. If it is love at all, it is a cherishing, protecting, maturing love which has the same kind of effect on the spiritual being of others as the light and heat of the sun have on their physical being.

Poems used

FOUR GIFTS

I come to you with four gifts.

The first gift is a lotus-flower.

Do you understand?

My second gift is a golden net.

Can you recognize it?

My third gift is a shepherds’ round-dance.

Do your feet know how to dance?

My fourth gift is a garden planted in a wilderness.

Could you work there?

I come to you with four gifts.

Dare you accept them?

1975

THE GREAT READER

Always a great reader

In bed,

Ever since I was a boy

I sat up late, hunched

Among the pillows, leaning

On my elbow in yellow light

Reading

Poetry romance philosophy magic.

Now

Decades later

Night after night, I read

The Book of You, turning

Page after illuminated

Page, dazzled

By the gold, lost

Among red and blue traceries,

Interlacing leaves

Flowers

Tendrils, vines,

Unicorns rampant, dragons, pink

And blue carpet-pages, gardens,

Fountains, faces, all the while

Desperately

Seeking to spell out the subtleties

Of a smile, the meaning

Of your life for mine

Maybe.

1970

Friendship was a key value in Bhante’s life. How do we relate to it in ours? How is it the whole of the spiritual life? How can we practice it in our situation?

Week 3 – Sangharakshita as Writer

Resources:

- My Relation to the Order (text, audio & Sangharakshita Complete Works – volume 2: ‘The Three Jewels I’ p.505)

- The Manu, The Buddha, The Guru and The Tertön (text, audio & Sangharakshita Complete Works – volume 12: ‘A New Buddhist Movement II’ p. 317

- Idols of the Marketplace (text)

- the slides used

Quotation from The Three Jewels

Chapter 8 – Doctrinal Formulae Sangharakshita Complete Works – volume 2: ‘The Three Jewels I’ p. 59

Spirit and letter are interdependent. Divorced from the living spirit of the Master’s teaching, the letter of the Dharma, however faithfully transmitted, is dead, a thing of idle words and empty concepts: separated from its concrete embodiment in the letter, the spirit of the Dharma, however exalted, lacking a medium of communication is rendered inoperative. In writing about Buddhism one should therefore be careful to pay equal attention to both aspects. The ideal account would in fact show spiritual experiences crystallizing into concrete doctrinal and disciplinary forms and these resolving themselves back into spiritual experiences. Full justice would then be done both to the letter and to the spirit of the tradition.

I have sometimes found it difficult to say whether I was a Buddhist who writes or a writer who was a Buddhist.

Poet, Teacher, Public Speaker, Editor, Translator: communication was a central preoccupation for Bhante, and his life was an outpouring of it. How do we communicate? What is our medium and our message?

Week 4 – Sangharakshita as Yogin

Quotation from Canto 34

From The Life & Liberation of Padmasambhava

The bhikșuni spoke:

“You understand in your request for power that all the gods are gathered in my heart.”

She then changed Dorje Drolod into the syllable HUM

and swallowed him, thus conferring blessings upon him.

Outwardly his body became like that of the Buddha Amitabha,

and he obtained the powers of the Knowledge Bearer of Life.

From the blessings of being within her body,

inwardly his body became that of Avalokitesvara,

and he obtained the powers of the meditation of the Great Seal.

He was then, with blessings, ejected through her secret lotus,

and his body, speech, and mind were thus purified from mental defilements.

Secretly his body became that of Hayagriva, Being of Power,

and he obtained the power of binding the highest gods and genies.

Quotation from Moving Against The Stream

excerpt from chapter 25 – A Secret Life

Sangharakshita Complete Works Vol 23 pages181-3

A biography or an autobiography – even a set of memoirs – can deal with the particular human being who happens to be its subject in a variety of ways. It can skate more or less lightly over the surface of his life, describing circumstances and chronicling outward events, or it can seek to penetrate beneath the surface and to explore in greater or less depth attitudes and motivations that are not immediately apparent and which may even have been concealed. It can also do both, either balancing narrative and psychological analysis or giving more weight to one or other of them in accordance with the inclinations of the author and the kind of life his subject has led.

Tibetan Buddhists have long recognized that inasmuch as a human life is lived on a variety of levels a biography should take account of all of them. The biography of a saint or a great teacher is therefore often divided into three parts, one giving his outer, one his inner, and one his secret

biography. The outer biography covers such matters as the saint’s birth, parentage, secular education, doctrinal studies, monastic ordination, and travels, while its inner and secret counterparts deal, respectively, with his spiritual practices and his transcendental attainments and realizations. It thus is a multi-layered work, reflecting in its highly organized formal structure the storeyed complexity of the saint’s or great teacher’s experience as he lived his life.

Though the ordinary person’s experience will be much less comprehensive in range, it is similarly stratified. Besides the outer world of work and play, there is the inner world of more or less conscious thought and emotion, great as the extent to which thought and emotion are bound up with external objects and events may be. There is also the world of dreams, recollections of which sometimes mingle with the stream of waking consciousness only, more often than not, to be quickly forgotten.

In my own case I have always been aware that I lived on different levels. Though neither a saint nor a great teacher, I too had an outer, an inner, and a secret life (secret in the Tibetan Buddhist sense) and had, therefore, in principle, not only an outer and an inner biography but a secret one as well. When I came to write the first volume of my memoirs, on which I started – rather light-heartedly – in 1959, there however was no question of my structuring them in accordance with the time-honoured Tibetan model, about which, in any case, I may not have known at the time. My life was far too complex to be divided up in any such way, besides which there were levels on which I dwelt only intermittently, so that no connected account of them was possible. Indeed it is doubtful whether it ever is possible for all the experiences of a person’s lifetime to be included in a single narrative line, greatly though such inclusiveness may be desired, and doubtful, therefore, whether any biography can really be considered complete.

In my memoirs I had a good deal to say about my outer life, rather less about my inner life, and very little about my secret life (again in the Tibetan Buddhist sense), so that the three divisions of traditional Tibetan biography were by no means equally represented. This was due partly to the fact that I happened to have a strong visual memory and enjoyed describing the scenes through which I had passed and the people I had met (I was definitely one of those for whom ‘the visible world exists’), and partly to the fact that, especially when working on my second and third volumes of memoirs, I could rely on reports of my activities that had appeared, over the years, in the pages of the Maha Bodhi, as well as on old letters, odd diary leaves, and my published writings on Buddhism. For my secret life there was no comparable record, save for a handful of poems of a more personal nature and the occasional cryptic reference in notebook or diary.

A reference of this kind occurs at the beginning of the entry I made in my diary for Monday 6 December 1965 – the second day of my visit to Glasgow. It reads, ‘Slept very little. Feverish most of the night. Mental state very clear. Extraordinary experience of Transcendental, such as have not had since leaving Kalimpong. Terry had experience of intensely heightened state of awareness.’ That is all. The entry goes on to speak of the arrival of tea (presumably brought by one of the guest house staff), breakfast, and the coming of Mr Pyle to settle our programme for the day.

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of this ‘experience of the Transcendental’, as of similar experiences of mine in the past, was its complete and utter discontinuity with any of my immediately preceding experiences. True, I had been speaking, only a few hours earlier, about the Buddha’s Vision of Reality, and about how that vision found expression, for purposes of communication, in the principle of universal conditionality, but even though I had felt very much in tune with my subject, as I usually did on such occasions, this fact alone did not suffice to account for the abrupt appearance, or descent, of an experience of such a totally different order. It was as though I was living, on another level, a secret life that normally had no point of direct contact with my outer or even with my inner life, and that by the time of my visit to Glasgow this secret life had reached a point where its accumulated energy, no longer able to confine itself to its own level, so to speak, had suddenly burst through into the two lower levels. The

sleeplessness, the feverishness, and the greatly enhanced mental clarity that accompanied the experience of the Transcendental were, as I well knew, all symptoms of that bursting through,

and as such they could be seen as the infinitely remote repercussions of that experience in my physical and mental being.

Meditation and ‘mystical’ experience was woven through the various episodes and activities of Bhante’s long life. How can we learn from his example in navigating the tension between the life of activity and the life of calm?

Week 5 – Sangharakshita as Lover

Resources:

- the slides used

Beauty played an enormously significant role in Bhante’s life and some of the expressions of his erotic urges have been controversial. What can we learn from all of this?

Week 6 – Sangharakshita as Revolutionary

Resources:

- the slides used

-

video of Bhante talking about what he’d like to be remembered for

Bodhisattva Ordination

from The History of My Going for Refuge

The bodhisattva ideal has attracted me from quite an early period of my Buddhist life. Indeed, it had attracted me from the time when, shortly after reading the Diamond Sūtra and the Sūtra of Wei Lang, I came across a copy of The Two Buddhist Books in Mahāyāna. The second of these books, which had been translated and compiled by Upasika Chihmann, Bodhisattva in Precepts (Miss P. C. Lee of China), was ‘The Vows of the Bodhisattva Samantabhadra’, which formed part of the Avataṃsaka (or ‘Flower Ornament’) Sūtra. This work I read repeatedly, and its picture of the infinitely wise and boundlessly compassionate bodhisattva must have made a deep impression on me for the words

Thought following upon thought without interruption, and in bodily, oral, and mental deeds without weariness

kept going through my head for days together. It was as though they embodied Samantabhadra’s – or any other bodhisattva’s – constant, unflagging fulfilment of his great vows through infinite time and infinite space. Seven or eight years later, shortly after my arrival in Kalimpong, I came across Śāntideva’s Śikṣā-samuccaya or ‘Compendium of Instruction [for Novice Bodhisattvas]’ and as a result was more strongly attracted to the bodhisattva ideal than ever – so strongly, in fact, that attraction is far too weak a word for what I then felt. The truth was that I was thrilled, exhilarated, uplifted, and inspired by the bodhisattva ideal, and my feeling for it found expression in some of the poems and articles I wrote during this period, as well as in chapter 4 of A Survey of Buddhism. There were two reasons for my being so strongly affected. In the first place, there was the sheer unrivalled sublimity of the bodhisattva ideal – the ideal of dedicating oneself, for innumerable lifetimes, to the attainment of Supreme Enlightenment for the benefit of all living beings. In the second, there was the fact that, as enjoined by my teacher Kashyapji, I was ‘working for the good of Buddhism’, and that I could not do this without strong spiritual support, the more especially since I received very little real help or co-operation from those who were supposedly working with me. This spiritual support I found in the bodhisattva ideal, which provided me with an example, on the grandest possible scale, of what I was myself trying to do within my own infinitely smaller sphere and on an infinitely lower level.

Padmasambhava (poem by Bhante)

Riding a tiger

The Guru came,

Smile fierce and friendly,

Eyes aflame.

Riding a tiger

From coast to coast,

With his vajra he scattered

The demon host.

Guru, great Guru,

Dispel my sin;

Hurl back the demon

Hordes within;

Transform them to powers

That protect the Right –

Thou, the Thousand-armed,

Thou, the Infinite Light.

To A Political Friend (poem by Bhante)

Thine is the outward action,

Mine is the peace within;

You forge the chains of faction,

I strive to wear them thin.

Through no dissensions narrow

Did you thus dearly go

With the swiftness of an arrow

From the stillness of this bow.

When your hot blood is abating

And anxious thoughts begin

You will feel me meditating,

And peace shall fold us in.

When the limit of your action

And the limit of my peace

Are joined by strong attraction

Our separate selves shall cease.

1946

Quote from 'Living with Kindness'

When we practise mettā it isn’t that there are literally beams of mettā radiating out from us as we sit and meditate, even though the image might be a useful one. Moreover, that central point of reference, that ‘core’ of the self, is in reality only a fiction. It is more useful to regard mettā as an outward movement of the self rather than from the self. As we continually expand the scope of our care and concern, the self is universalized, one might say, or expanded indefinitely. This does not mean that we have to transform our sense of who we are according to an idea of how we should be that is quite alien to how we experience ourselves. It is rather that our direct experience of ourselves should be that we are continually going out to be aware of and concerned for the well-being of others, not fixed on any single point of identity.

Quote from 'A Stream of Stars'

To me it seems more obvious than ever that if we are to generate enough enthusiasm and inspiration to enable us to break through the bonds of our own individualism, as well as through the strongly anti-spiritual tendencies of modern life itself, we need the Bodhisattva Ideal. Only the Bodhisattva Ideal can carry us beyond ourselves and the world – and back again into them on a totally different basis.

Guru Yoga Prayer

O my own Immediate Shri Lama Rimpoche

(Abiding) within the lotus of my heart,

May you never separate from me, but

on the contrary, remain inseparable!

Grant me siddhi of body, speech and mind!

Throughout all births may I have an excellent Guru and,

From him never separated may I practise the Shri Dharma!

And fully accomplishing the good qualities

of the Paths and the bhumis

May I speedily attain the Vajradhara state.

From this evil mind of mine speedily (liberated),

May I speedily become the Guru-Buddha,

And may I lead all beings without exception

to the Guru-Buddha’s Abode.

O Shri Guru, as are Thy Kaya(s),

Length of life and abode,

And Thy resplendent lakshanas,

so also may I be

In one interview Bhante said that his contact with Dr Ambedkar and his people introduced into his conception of the Dharma the element of Social Responsibility. His founding of the Triratna Buddhist Order and Community was an audacious fresh start for Buddhism intended to make it a powerfully transformative agent for self and for the world. How do we think about and express this central aspect of his life and teaching?

Jnanadhara

Originally from New Zealand where he met Triratna at the Wellington Buddhist Centre, Jnanadhara now lives in Dublin, Ireland. He joined the Order in 2003 after spending some years working at Windhorse Trading in the UK. He served as chair of the Dublin Buddhist Centre for twelve years before taking on being International Movement Coordinator, a new role that seeks to join up our Buddhist community worldwide.

Kindly supported by Future Dharma

Testimonials

The is the second time we’ve run the course.

Here is what some of the participants from the first course said:

Khemabandhu (chair of Adhisthana)

It was great simply to come together as Chairs from all over the world and have mutual support in the discussion groups while at the same time learning some very practical and helpful skills from others who have so much more experience, skills that I could immediately put to use.

Suvarṇachandrā (chair of Helsinki Buddhist Centre)

The course was in my view just what was needed. We heard well prepared talks about different topics the chairs of centres are working with. Then we had a chance to meet as a chapter with four or five other chairs around the world, and to guide the conversation we had well thought through questions. This is really what I as a chair need, and sounds like others as well, so it would be good to have some sort of continuation to this, there are lots of topics chairs need to know.

Thank you Jnanadhara!

Ananta (chair of New York / New Jersey)

This has been an excellent course and one that has come at an ideal time for me as I have taken on the Chair role. Jnanadhara covered a lot of important and helpful ground around what it means to be a Chair and some of the challenges and pitfalls to navigate. I’m coming away with a clearer sense of what my role is and how I might face challenges as they arise.

Muditadevi (chair of Oslo Buddhist Centre)

I found the online chairs course with Jnanadhara very inspiring and useful for me as a chair. I got useful tips for preparing and chairing meetings and inspiration to see the spiritual practice in being a chair. I very much enjoyed meeting up with other chairs too and sharing our experiences. It was inspiring hearing Jnanadhara share his personal experience as chair.

Prajnaketu (chair of Oxford Buddhist Centre)

This course came at a perfect time for me, as I’d just taken on the Chair at the Oxford Buddhist Centre. I found it comprehensive – in covering all the aspects of the role, from chairing meetings to the spiritual practice of running a sangha – and deep, drawing on Jnanadhara’s hard-won experience. I feel his input has already helped me to pre-empt some common pitfalls, as well as preparing me well for the wider dimension of life as a Chair. It was also helpful and enjoyable to chew over elements of this unique responsibility with others in the same position. I’d gladly do it again!

Sudaka (chair of Suryavana Retreat Centre, Spain)

Really enjoyed the recent five week course for chairs led by Jnanadhara. Principally for me, as a Chair out at the periphery of the Triratna heartlands, it gave me a wonderful opportunity to share, laugh and learn with others. The Chairs are such a valuable group within Triratna and it was a real balm and support for those of us participating. The content was concise and thought provoking. Thanks and hope to do again.

Vajracaksu (Triratna Istanbul)

I wasn’t able unfortunately to go to all the classes of the recent chairs course but did manage three sessions. I found it a very useful course and just loved listening to and sharing thoughts and experiences with other chairs, we are in the same, very particular boat! Jnanadhara poured a great deal of thought and love into the course and his very helpful presentations, respect to him. I’m looking forward to the next similar online event.

Dayavāsīnī (chair of Tierra Adentro & Pachuca Buddhist Centre)

After being in charge of a couple of small local Triratna projects in Mexico for more than 14 years I much appreciate the opportunity of sharing experiences through the Chairs Workshop led by Jnanadhara. Not only the experience of sharing with other Order Members , but also the opportunity to learn more about their experiences and particularly the way they manage their council meetings, meant a refreshing and significant encounter.

Maitridevi (chair of Taraloka Retreat Centre)

I’ve been listening to the recordings of your International Chairs course whilst I’ve been weeding the garden, and I’m really enjoying them. I wasn’t quite sure what to expect, but it feels like lovely cosy sessions where you relay all the wisdom you’ve gleaned from your years of Chairing and pass it on to the rest of us. There’s something very comforting listening to you say things like ‘as a Chair you’re bound to attract criticism – but don’t worry… you can always practice patience…’ etc.

Just your simple but thorough explanations on how to run Council meetings are – for me – a helpful reminder of best practice. Listening to you does also make me aware of the ways in which retreat centre chairing is different from urban centre chairing (I think retreat centre chairing might be easier!), but still it’s all interesting and helpful.

Well done for organising it all – I imagine you’ve got really good feedback as I think that this course is very helpful and relevant.